KC Jam interview 2019

Kansas City Jam Magazine Interview, Dec. 2019

The Matt Kane Interview for JAM Magazine September 2019 – by Joe Dimino

The dreamer is alive and he plays the drums in New York City. If there was ever a modern-day success story of a jazz cat that came from small town beginnings in Hannibal, MO and wove deep roots into Kansas City before moving on to the mecca of New York City, it is drummer Matt Kane. He’s the ultimate story of a kid from the land of Mark Twain that made it to the definitive city that brings those dreams to life.

Everything began for you in Hannibal, Missouri. Talk to me about those beginnings.

Hannibal is a very small town. But growing up in there in the 70s and 80s, you could dream. The horizon was wide. You could look out across the Mississippi and dream big. There were no distractions. For me, music started downstairs in the basement with a record player. The was something mystical about music. It mesmerized me. It was and still is an alternate universe or dimension that is timeless and boundless. Music captured me in an intangible sense. I spent hours with a turntable and my folk's collection of 45’s; Motown records, the Beach Boys, Beatles, 60s rock and R&B and a lot of soundtracks.

Music in films really interested me. Especially in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” music was woven into the narrative of the film. I thought it was cool they communicated with aliens through music. So it was music first and then the drums came along.

The drums never existed as a separate entity. The drums came later. The drums and the feeling of rhythm was the clincher for me. I just loved rhythm and sound; crickets, the ticking of a clock, footsteps, a dripping faucet, squeaking feet on a basketball court, it’s everywhere all the time. And the drums as an instrument, well, it was empowering to touch a drum. I felt it inside my body. People respond to rhythm, physically. The sound, the feeling and the majesty of the drum totally took me. It’s been that way ever since.

You already touched on it some, but more pointedly, why was music your future?

Music chose me. It was something that I could do, assertively. I could watch sports on TV, but I really couldn't do that like I could music. I could play music and create something. You know, when you are really young, you don't think about it making a living or anything like that, you just love it. Early on, my cousin Kevin Allen, who lived over in Quincy, Ill., was a prodigy on guitar, banjo and dobro. He was touring when he was like, 10 years old, playing the Grand Ole Opry and tv shows and stuff. That got my attention. It just seemed natural to become a musician and nothing else ever entered my mind, not once. Then getting those first gigs at the age of 15 it felt like that’s what I was supposed to be doing and it kept going. I just loved that connection of playing with a band. When you make music with other people, you are creating something bigger than yourself. You are creating something that is making other people happy. When you make other people happy, you are going to be happy, too. That's the biggest part of it for me, creating something larger than oneself, the collective vibe.

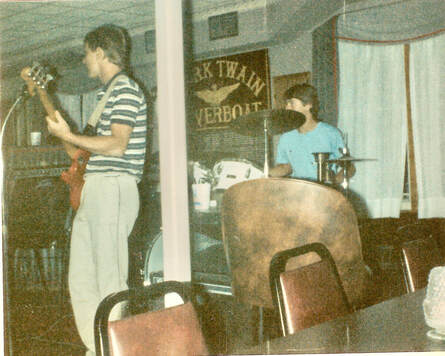

Talk to me about that first gig on the Mississippi River.

In the summer of 1986 I was 15, my mother heard through a friend that they were putting a band together and needed a drummer. So, I auditioned and they were shocked that I could play and played with a lot of energy and fire, really going for it. It was like I had been preparing for that my whole life, like finally, people to play with instead of just records! In just a couple weeks they started to get gigs and and started putting money in my hand to play music, I thought 'wow. this is great!’ The fist gig was actually on the Mark Twain riverboat there in Hannibal.

Jazz had travelled up and down the Mississippi River on riverboats 70 years prior to that, innovative musicians like Baby Dodds and Louis Armstrong had taken the music up the river on those boats. Dodds even mentions Hannibal in his autobiography. We played a mix of country, blues, southern rock and some pop tunes. That was really the beginning of it. I remember the river boat was kind of rocking back and forth. The drums would tilt back and slowly shift forward. I could feel that boat moving around. That was kind of a trip. The boat was a Mark Twain excursion, which meant the boat went out by Jackson's Island and other spots mentioned in the stories. Man, I bought into all the Mark Twain stuff 100 percent. I read the books when I was a kid and wanted to be Tom Sawyer. I loved those books. I really wanted to do that. Be the adventurer. Tom Sawyer was my biggest childhood hero, to be totally honest.

The dreamer is alive and he plays the drums in New York City. If there was ever a modern-day success story of a jazz cat that came from small town beginnings in Hannibal, MO and wove deep roots into Kansas City before moving on to the mecca of New York City, it is drummer Matt Kane. He’s the ultimate story of a kid from the land of Mark Twain that made it to the definitive city that brings those dreams to life.

Everything began for you in Hannibal, Missouri. Talk to me about those beginnings.

Hannibal is a very small town. But growing up in there in the 70s and 80s, you could dream. The horizon was wide. You could look out across the Mississippi and dream big. There were no distractions. For me, music started downstairs in the basement with a record player. The was something mystical about music. It mesmerized me. It was and still is an alternate universe or dimension that is timeless and boundless. Music captured me in an intangible sense. I spent hours with a turntable and my folk's collection of 45’s; Motown records, the Beach Boys, Beatles, 60s rock and R&B and a lot of soundtracks.

Music in films really interested me. Especially in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” music was woven into the narrative of the film. I thought it was cool they communicated with aliens through music. So it was music first and then the drums came along.

The drums never existed as a separate entity. The drums came later. The drums and the feeling of rhythm was the clincher for me. I just loved rhythm and sound; crickets, the ticking of a clock, footsteps, a dripping faucet, squeaking feet on a basketball court, it’s everywhere all the time. And the drums as an instrument, well, it was empowering to touch a drum. I felt it inside my body. People respond to rhythm, physically. The sound, the feeling and the majesty of the drum totally took me. It’s been that way ever since.

You already touched on it some, but more pointedly, why was music your future?

Music chose me. It was something that I could do, assertively. I could watch sports on TV, but I really couldn't do that like I could music. I could play music and create something. You know, when you are really young, you don't think about it making a living or anything like that, you just love it. Early on, my cousin Kevin Allen, who lived over in Quincy, Ill., was a prodigy on guitar, banjo and dobro. He was touring when he was like, 10 years old, playing the Grand Ole Opry and tv shows and stuff. That got my attention. It just seemed natural to become a musician and nothing else ever entered my mind, not once. Then getting those first gigs at the age of 15 it felt like that’s what I was supposed to be doing and it kept going. I just loved that connection of playing with a band. When you make music with other people, you are creating something bigger than yourself. You are creating something that is making other people happy. When you make other people happy, you are going to be happy, too. That's the biggest part of it for me, creating something larger than oneself, the collective vibe.

Talk to me about that first gig on the Mississippi River.

In the summer of 1986 I was 15, my mother heard through a friend that they were putting a band together and needed a drummer. So, I auditioned and they were shocked that I could play and played with a lot of energy and fire, really going for it. It was like I had been preparing for that my whole life, like finally, people to play with instead of just records! In just a couple weeks they started to get gigs and and started putting money in my hand to play music, I thought 'wow. this is great!’ The fist gig was actually on the Mark Twain riverboat there in Hannibal.

Jazz had travelled up and down the Mississippi River on riverboats 70 years prior to that, innovative musicians like Baby Dodds and Louis Armstrong had taken the music up the river on those boats. Dodds even mentions Hannibal in his autobiography. We played a mix of country, blues, southern rock and some pop tunes. That was really the beginning of it. I remember the river boat was kind of rocking back and forth. The drums would tilt back and slowly shift forward. I could feel that boat moving around. That was kind of a trip. The boat was a Mark Twain excursion, which meant the boat went out by Jackson's Island and other spots mentioned in the stories. Man, I bought into all the Mark Twain stuff 100 percent. I read the books when I was a kid and wanted to be Tom Sawyer. I loved those books. I really wanted to do that. Be the adventurer. Tom Sawyer was my biggest childhood hero, to be totally honest.

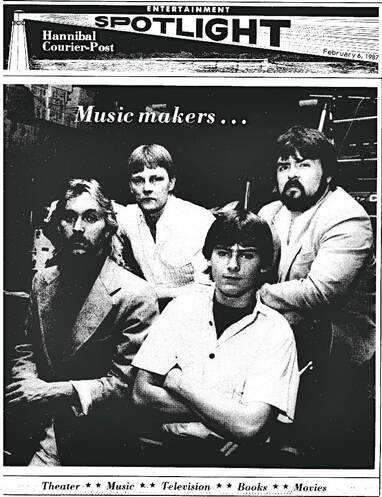

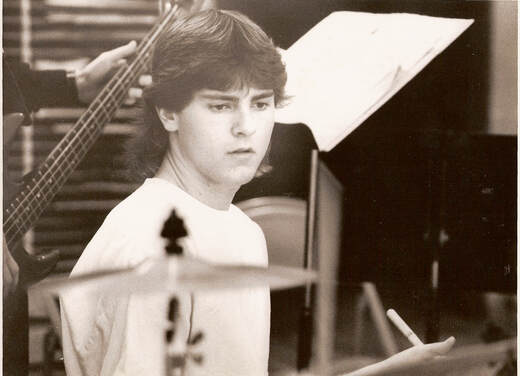

1989 All State Jazz Auditions

1989 All State Jazz Auditions

Talk to me about getting All State Jazz Honors.

Growing up in Hannibal was very isolated. There were no jazz musicians around, no clubs, little contact with the outside world really. After some basic snare drum lessons from some of the high school kids who kept moving away to college, I was largely self-taught from age 12 to 18, mostly learning from records and piecing it together in the basement with a drum set, turntable and cassettes, playing in school band and playing gigs with local country and rock bands. As I started getting older, I began getting anxious wondering about the future. There’s a big gap between Hannibal and New York, or even St. Louis or Kansas City. I just can't go waltzing into a big city and start playing. I started seriously wondering how I would get out of Hannibal. My grades were not so good and we didn’t have money for schools like Berklee or North Texas.

Then I became aware of the Missouri All-State Jazz auditions. So, each year I auditioned and guys from St.Louis and Columbia won the chair. I felt like the country kid competing with the city kids, they had it more together and it was really frustrating wondering how to catch up with them, especially without a drum teacher/role model. But by senior year, I was determined, came with a lot of urgency and won. That was huge because I got to learn from Bob Curnow, who had just put out an album of big band arrangements of Pat Metheny’s music. It was the first time I became aware of Pat's music. It was really the first time I played in a band of that caliber. It was extremely humbling. I found out that I really had a lot to learn. It made me even more aware of my country-ness, so to speak. Through that experience, the UMKC jazz director Mike Parkinson invited me to audition at the conservatory, which I’d never heard of. I thought I’d maybe go to MU in Columbia or St. Louis U to play in a marching band or something. But, UMKC came along, I had a great audition and earned some scholarship money. So, that All-State experience was my ticket out of Hannibal and on to KC. It felt destined. At that time, I had a real sense of urgency, a ‘do or die’ type mentality. In fact, I graduated from high school on a Friday night and the next Monday I was living in Kansas City. I got a key to the practice room at the PAC on campus and started shedding immediately.

You say that Kansas City chose you and this was the place you were destined to come to. Talk to me about that and some of the people that were big in your KC life like Lori Tucker, Ida MacBeth, The McFaddens, Sons of Brazil, Bob Bowman and Ahmad Alaadeen.

Aw man, it all started with that scholarship to UMKC. Just a couple of months after arriving in Kansas City, I was recommended to Lori Tucker's band. She had a four night a week gig at the Mariott on Main St., so I was immediately working a lot, to my surprise. It was my first introduction to the blues feeling of KC and to play with anybody that had that so deeply and I just learned a ton playing with Lori. She is such a phenomenal singer and her spirit is so beautiful. We had such a great time. Also in that band was Tom Pender on guitar and Paul Roberts on piano/keyboards and James "Ham" Strawn on percussion. So, Lori's gig in conjunction with UMKC program was the perfect place to go to after Hannibal. It wasn't as daunting as New York and I would want it no other way. I have family in Kansas City, too. At UMKC there were a lot of legendary musicians who came through there. Mike Parkinson deserves a lot of credit for getting that UMKC jazz program going. He was bringing in Gerald Wilson, Bob Brookmeyer, Clark Terry, Lew Soloff, Phil Woods, Claire Fisher, Carmell Jones, Kenny Werner, John Fedchock. They were coming in and doing week-long workshops with us. That was colossal. I mean, going from playing a VFW hall in Hannibal in the spring to playing a concert with Gerald Wilson in KC in the the Fall, it was surreal and exciting and humbling.

The Foundation was crucial to my development around this time, mostly because of a bassist named David “Daahoud” Williams. I went down there and was sounding really bad and he stopped the band cold, turned to me and said “Kid’s night is on Wednesday night.”. And it was Saturday night! It was brutal and I didn’t go back for a year or more. Finally, when I went back and was swinging, he was the first one to be like “Where did you come from?!” And from then on I had Daahoud’s acceptance, which meant a lot to me. And I watched him carefully; how he physically got his beat on the bass, his body motion, how and where he felt the beat. Even watching Daahoud dance around the room when he wasn't playing, he'd sing bass lines out loud and he was a real trip. It was a major education. There were many, many early morning jams at the Foundation, I loved it there and the feeling of being accepted there gave me hope that I could play this music. The Foundation represented the truth to me. It was old, old school.

After my Junior year at UMKC things opened up a lot, I went to audition for The McFadden Brothers. They had a five-night-a-week gig down at the Allis Plaza. Even then, a five night a week gig was rare. Working with Ronnie and Lonnie was huge. The main thing was that Lonnie wanted that fire. At the time, I was really broke. I was living in a warehouse basement off 19th and Broadway. I had made some unwise moves that landed me there. So, when I heard about that audition, I went for it like my life depended on it. Lonnie really dug that. So he and l will forever have this bond because Lonnie saw something. I was still kind of rough. I played loud and combative. A lot of folks were not crazy about the way I played. I was a loose cannon, so to speak. But Lonnie saw something in me and took me in. And Lonnie would sock it to us. I'm not lying. There were nights where we would have a band meeting and Lonnie would tell us that this wasn't cutting it, that we needed to step up. It was serious. No sleepwalking or half-stepping. Lonnie just wanted us to play. The show was high-octane intensity. He said he would never tell us to tone it down. For about 8 months we played 5 nights a week. We just played our asses off and that's what Lonnie wanted. I love him for that because he didn't squash us and let us make our mistakes. and there was never any joking on the bandstand, it was all business. Which to this day, I don't like joking on the bandstand, for me it's serious fun, not glib or flippant, but "let's do this" kind of attitude. When I see him to this day, it's like no time has passed. I have a ton of respect for him and how he lives and conducts his thing. Lonnie and Lori Tucker are like family.

Later I joined Ida McBeth’s band and she controlled an audience like nobody I’ve ever seen. Ida was a master of connecting with people. She could hush an unruly audience with a poignant story in between tunes, she is really a master storyteller. As a vocalist, Ida was unmatched in town. She could tear the house down at will, she could make people cry. And years later, Ida was in NYC right after the 9/11 attack, I was playing a gig and she and Rob Whitsett came to see me. I was so happy to see somebody from home, it meant a lot to me that she came.

Then there’s Stan Kessler and Bob Bowman, I love those guys. Stan was really cool to me and gave me tapes Sons of Brazil’s repertoire and eventually I played some gigs with them which meant the world to me. I followed that band around KC alot. Doug Auwarter was a big factor in that because he'd really studied the brazilian thing deeply. Stan’s a wonderfully lyrical trumpet player and creative spirit. He’s a good bandleader, too. Bowman, well, he was the very first musician I met in town when I was 18, down on Southwest Blvd. at a place called “The Tuba”. I was shocked when I heard him with his band “Interstring” with Todd Strait, Danny Embrey and Rod Fleeman. I’d never heard anybody play like that. They were incredible influences, especially the way that group played together, they were like one big musical amoeba. It was just on fire. Eventually he called me to do some gigs with the band which was like a dream come true, I loved that band and their repertoire was so deep. Their run at “The Tuba” was legendary, man. Stan and Bob embody the KC spirit, it wouldn’t be the same scene without them. They were very cool to me at a time when my playing needed a lot of work but they still gave me a shot and I’ll always be thankful for them.

Then there’s Stan Kessler and Bob Bowman, I love those guys. Stan was really cool to me and gave me tapes Sons of Brazil’s repertoire and eventually I played some gigs with them which meant the world to me. I followed that band around KC alot. Doug Auwarter was a big factor in that because he'd really studied the brazilian thing deeply. Stan’s a wonderfully lyrical trumpet player and creative spirit. He’s a good bandleader, too. Bowman, well, he was the very first musician I met in town when I was 18, down on Southwest Blvd. at a place called “The Tuba”. I was shocked when I heard him with his band “Interstring” with Todd Strait, Danny Embrey and Rod Fleeman. I’d never heard anybody play like that. They were incredible influences, especially the way that group played together, they were like one big musical amoeba. It was just on fire. Eventually he called me to do some gigs with the band which was like a dream come true, I loved that band and their repertoire was so deep. Their run at “The Tuba” was legendary, man. Stan and Bob embody the KC spirit, it wouldn’t be the same scene without them. They were very cool to me at a time when my playing needed a lot of work but they still gave me a shot and I’ll always be thankful for them.

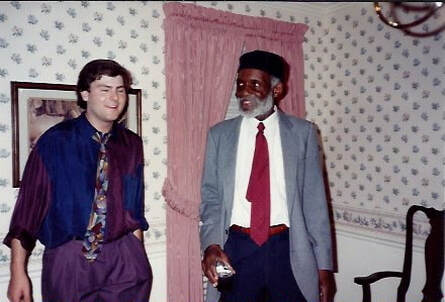

Speaking of family in Kansas City. Let's talk about Ahmad Alaadeen. He is like that mythical jazz Jedi master. He brought so much good to so many here in Kansas City. Talk about your time and memories with him.

I first met Alaadeen at UMKC and then a couple of years later I heard him on the Plaza playing with a drummer named Don Mumford. And Mumford was a real trip. He played with the likes of Abdullah Ibrahim and Sun Ra. So, I went down there to hear Mumford and that was the first time I ever heard Alaadeen play his original music. At the time, Alaadeen was really the only person in Kansas City that was writing and presenting original music the way he was doing it. He wasn't a sideman for anybody or putting himself out there any old way for a buck. I mean, he picked his spots judiciously. He presented his vision as an artist through his original music. There was something different about his music than anybody else in town. It was uniquely Alaadeen. He put a lot of contemplation and intention into his music. That’s just talking about him as a composer. As a player, he was this link to the future and the past. He had one foot in the future and the other foot in the blues and the life that he had lived. Alaadeen came along in a certain window of time where there was a lot of spirit from the bebop era, the hardbop era and things were also looking forward with Miles' music and Wayne Shorter and of course Trane. Alaadeen's music spanned a lot of that. When you heard Alaadeen play, you heard a deep root in the blues come out and all of Kansas City in general. I don't think any musician can come up in Kansas City and not have a connection to the blues. You hear it from everyone. Whether it's Alaadeen, Metheny, Bobby, Logan. Whoever it is, they have that thing. So, after a couple of years, I got my nerve up, called him and said I wanted to be in his band. He told me to be at The Foundation on Tuesday at 2 O’clock. I went down and rehearsed with him and then was in the band, though there was never an official “you’re in”. I was a little nervous and on edge most of the time, which was good. He didn't say more than three words, so you really didn't know what he was thinking. He said more with his silence, leaving you to think it through for yourself.

This was the tail end of the apprenticeship era, when young cats worked as sidemen for several years before they put out their own records and led their own bands. Now, kids are booking gigs as leaders when they're still in high school, putting out records when they're like, 12 years old. That wouldn't have flown back in the 50s and 60s. The apprenticeship era ended a good many years ago, but Alaadeen made sure he kept that in place for Kansas City. We were fortunate.

Alaadeen knew that the music was going to live through the young cats. Some bandleaders in Kansas City would not be hiring us young guys. Alaadeen was one of the few bandleaders that would give young guys a chance to open up and play. Especially on his original music and that's a big deal. When you present your original music and put it in the hands of a 22-year old. That says a lot. There are parts of my experience with Alaadeen that I don't understand yet until maybe I'm a little older and more experienced. He treated us like grown men. You come to the gig suited and booted and no questions asked. It’s assumed you’re going to handle your business. This ain’t kids’ music here. That instrument you’re playing ain’t a toy. One time a cat showed up to the gig and forgot his suit pants and Alaadeen wouldn’t let him on stage, we played without him and he had to sit outside in the van. It was old school.

Sometimes the lessons are in all the other details. Every now and then I would go over to his apartment and we would listen to music. I would always ask him what I needed to do to get better and he would say something short and cryptic like 'just keep livin.' I was young and wanted concrete information like riding my cymbal a certain way or do this with the left hand. He never spoke on that. His way was for us to go figure it out. He put us on the bandstand and gave us the learning opportunity, so it was up to us. Because if you can't figure it out yourself, nobody can do it for you. No school, no books. The answers are in the music. Ultimately that's what any great musician must do. Make the most of your opportunities and be truthful and honest with yourself. If you don't know the truth for yourself, how is someone going to know it for you? That was a big take away from being around Alaadeen. He was the genuine real deal and I’m thankful to have been touched by him.

Why was New York City the next step in your music evolution.

All the signs always pointed to New York. Any time I picked up an album and looked at the back of it and it said it was recorded in New York. That's where all of my heroes were playing. Elvin Jones, Roy Haynes, Billy Higgins and Al Foster. Everybody was there. They weren't coming through KC. I wanted to experience them. The one question I still keep in mind to this day is, “how can I grow?”. If you are really honest with yourself and seeking the truth, you don't stop looking for that. It’s what took me from Hannibal to KC. It felt to me that the truth was in New York. I knew there was not going to be a welcome mat laying out there for me. I knew it was going to extremely difficult, but I felt in order to keep growing New York was the place to go. That says nothing bad about Hannibal or Kansas City at all, but New York was simply the place to go. The people I admired, that's where they went. People were even telling me to go. I remember one night at a club in the 18th and Vine District called Club Mardi Gras playing with Gerald Dunn. At the end of the gig, the bartender came up to me and said “playing the way you play, you need to be in New York”. So, I tried it in 1993 and totally crashed and burned. It snowed everyday for three months and I went broke and ended up coming back to Kansas City and finishing college. In 1997 I went back for the second time and determined and prepared and was able to stay.

Talk to me about the second time around. Your early experiences, how you gained steam and those profound experiences that made you grow.

Things went south on day one. My living situation fell out I had to scramble to find a place to live. Just to find a place to live, this would sum it all up. First, I crashed in a rented living room in Queens for six months and then when I geared up to get my own pad I went and answered an ad for a place in Brooklyn. They said they were showing the place at 6, then at 6:30 and told me to be there at 7:00 pm. I put the phone down, went straight to the place and beat everyone else there. They showed me the place and I wrote a check on the spot. Then the others started showing up wondering what happened. That's how tenacious it forces you to be. If someone says be there at 4, then you should be there at 2. If you want to walk in New York, you can't bullshit. You have to claim your space and do it. Everything takes a little extra. Sometimes it takes a lot extra. New York forced me to define the 'why'. To re-evaluate my purpose on a daily basis.

The power of purpose is very strong and it carries you through to the truth. Your purpose has to be on point or else you're going to have a real tough time. I hit a lot of walls and had some very tough times. There was definitely no overnight success. New York is not just one jazz scene. It's many jazz scenes. Pockets are very tight. Cliques are very tight. You could be the baddest, greatest player in the world, but not everybody is still going to like you. One circle may like you and the other may say it's not their cup of tea. There are multiple challenges with the scenes in New York. I just started carving out a spot for myself. I took classes at the New School and gigs were few and far in between for the first year or two. I leaned on my guitar quite a bit. I took classes at the guitar study center at the New School. I probably played more guitar than drums during my fist three years in New York. In a way, I'm glad it happened that way. I wrote a lot of my early songs then. New York forces you to look within yourself because you are not going to get a whole lot of outward support. You really have to buck up and look within and find ways to get your creativity out.

Talk to me a little bit about 28th Street. The view of a brick wall.

After a couple of years in Brooklyn in the late 90's, I caught wind of artist housing that was opening up on 28th Street between Fifth and Madison. I applied for it and since I was a New York resident for a couple of years and my income was at the right level, I got an apartment there and the view was of a brick wall. But, I was thrilled to live in Manhattan with the Empire State Building six blocks away. I never dreamt that anything like that would ever happen for me. If you're tenacious enough, things happen. You can’t just hang out in the barbershop and not get a haircut. Good things started to come. I was living in Manhattan. I was gigging finally.

After the coolness wore off, that brick wall made me feel like I was incarcerated. It was a tiny one room cell and you're just in it. Then, living through the 9-11-01 period was really tough, I watched it unfold in clear sight, standing on 23rd St and 5th Av. It haunted me. The city changed, people changed. So, being incarcerated in that little Manhattan room forced me to dig in deeper and further within myself to be creative and deal with the constant pressure cooker of living in New York. It was a eight-year period. It was 1999 to 2007 and without a car. I took the drums around on a wheelie cart. So basically I played a bass drum, a snare drum, a ride cymbal and high hat for seven years. That was very challenging. There was really nowhere to practice. There was a little space in the basement where you could go, the musicians fought over it all the time and it smelled like beer and urine. It was a very New York thing. It was a blessing and a curse at the same time. There you are living in midtown Manhattan living the dream of a lifetime, but you are incarcerated in a cell. There were good things to come out of it, too. I just hunkered down and wrote a lot of music during that period. There is an energy thing in Manhattan. When you are in Manhattan, you just feel like creating. I don't know what it is, but it's in the air. It's like create, or that creative energy will eat you up. So, to keep that energy from collapsing in on you, your mind needs to travel. So, when you are incarcerated in a concrete valley in the city, year after year, your mind simply has to travel. I just connected with my guitar and wrote a ton of music during that time. A lot of the songs on my latest album 'The Other Side of the Story' came from that period.

Talk to me about the Brazilian, African, Hip-Hop Identity you took on.

I re-evaluated my relationship to music and jazz. I was asking myself 'what am I trying to do here?' At that time, the jazz scene started to feel quite pretentious to me and hostile. You'd walk into the jam sessions and cats were just really uptight. I knew it wasn't just me because that was the vibe most of us felt. Cats started to look outside of jazz. So, I needed something that was just going to make me feel good. You know what I mean? Jazz didn't feel good to me. It felt like cats were playing at each other rather than with each other. So, I started to hang out in these Brazilian clubs. I got my first taste of Brazilian music through the Sons of Brazil. So, when I started sitting in on the New York Brazilian scenes, the Brazilians were saying it sounded like I really knew how to play their music. So, I started hanging with them and got calls from Brazilians. So, from about 2002 to 2008, that was the majority of the gigs I played. I was playing tons of Samba gigs and was learning the repertoire. I just loved it. I love Brazilian people. I traveled down to Brazil to learn from the source. Their music has optimism and ponigantcy, it spoke to me emotionally. They accepted me and that was very welcoming.

At the same time, I was playing congas in these massive NYC dance clubs. I started producing “beats” and hip-hop flavored music on my recording rig at home. The word started getting out a bit, so I started producing some stuff for some rappers. Next thing I knew, my apartment on 28th Street became this hub where emcees would stop by for me to zip up their tracks. I was happy to do it. I was recording all the time. I still have a huge library of beats that I made. It became an obsession. It was another way to keep from going crazy. Ultimately it was hard for me to sustain anything in hip hop because there was zero money. I simply couldn't find a way to monetize my efforts. I had a great time and learned a lot. You know, when you camp out with one beat and listen to it for 8 hours a day, it changed my perception quite a bit. I’m very thankful for that period of time away from jazz. It was a necessary thing that simply had to happen. I think a lot of jazz musicians go through that. You got to work within the time that you live in. I lived through the era of De La Soul, Digable Planets and Tribe Called Quest and that whole conscious hip-hop thing. There was always a part of me that felt like I had something to say in that realm. That’s the music of my generation. So, I had my say and had a lot of fun. Then, like a switch being flipped, I couldn’t listen to another computer generated beat. Ultimately jazz called me back.

That would lead to the great Dr. Michael Carvin. Talk to me about this relationship and how it has led up to the present day.

I hit a wall in my New York existence in 2008. I needed help. Since arriving in the city, my experiences with “name” teachers was confusing and some of them had really burnt a lot of young cats just to feed their ego. When I met Carvin and walked into his studio, he had pictures of his successful students on the wall. I knew this was the right place. Even talking to him on the phone before I met him, his voice cut through the phone like a razor. He booked a lesson with me and the last thing he said was, 'Look, only a failure makes an excuse. I will see you on next Tuesday at 1pm.' CLICK. I thought 'oh wow.'

I had been hearing about him for years and this is why. When I walked into his studio, I could just feel that he took his responsibility and duty to help you be successful as serious as he took anything in his life. Immediately from Carvin I started to see that it's all one thing. He talked about, and still does, discipline. The way you live your life, the way you treat people, the way you present yourself, the way you keep your home clean, the way you conduct your business, the way you play - it's all one thing. So, it's your duty. If you're going to do it, then do it. Immediately that was the vibe I got from Carvin.

I told him my whole life story and how I had hit a wall, struggled with alcohol and was frustrated and simply didn't know what to do. He listened. First, he helped me to like and accept myself. For me, New York was one giant identity crisis. First I'm playing jazz gigs, then I'm playing hip hop gigs, then I'm on Brazilian gigs. I'm bouncing around. I don't know who I am. So, he settled me down and helped me look in the mirror and like who I was. No one had ever done that for me before. All the other teachers pointed me away from myself, “transcribe this” or “you gotta peep so-and-so’s ride beat” or whatever. No one said that the answer was within me. No one did that for me, except Carvin. He saw that as his duty. Because if I failed, he would fail. I succeed, he succeeds. WE succeed. The language of “We” not “me” or “I”. Now, that’s a teacher. I defined my dreams, many of which I had tossed aside because I was frustrated and confused. Dreams matter.

Carvin's whole thing is that he did the scene, the Vanguard, Sweet Basil, The Village Gate and did the streets and now it’s time for me to do the same. He's giving it to me. He's going to empower me and show me who I am. And then, I'm going to be unstoppable. When he looked me in the eye and said that I was great, it was wonderful. He never pointed me in any other direction except within myself as the source of success and power. A great drummer is a great drummer and we got lots of them. I’m not saying anything negative about any great drummer. Michael Carvin is a master drummer. A master drummer can show another how to be great. A master can reveal another one's greatness to themselves. That is beyond rare. You don't see that anywhere. So that's why he's a master. He can show you how to be great, but you have to do the work. You have to keep your discipline at all times. That’s what he revealed to me. He calls his teaching philosophy 'each one, teach one'. He teaches one student and that message goes out to another student and to another and another. He wants to perpetuate great drummers. He doesn't see any of us as his competition. He wants great drummers and he gets them because he knows how to forge them through discipline and self-realization.

Talk to me about coming back to Kansas City. Playing at the Blue Room and the Green Lady Lounge with John Scott. There is a culture that you continue to come home to. So, talk to me about that.

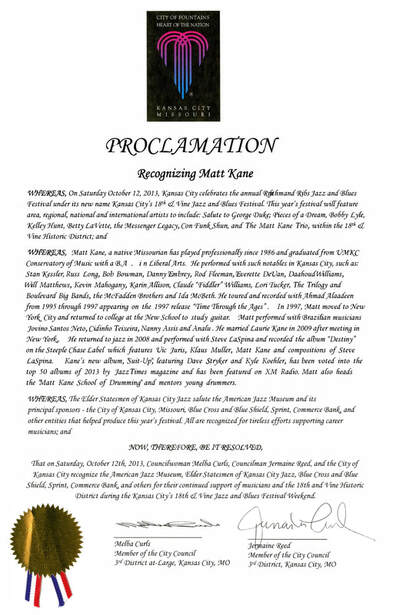

I purposely stayed away from Kansas City for about eight years because I didn't want to come back and do a standards gig or a sideman gig. It had to be cohesive because presenting a concept is key. An audience deserves that. More importantly, the MUSIC deserves that. So, I finally came back in 2011 for a Blue Room performance that went really well and started a great partnership with a great young bassist Ben Leifer. Then, I was invited back to the 18th and Vine Heritage Festival in 2013 to be the artist-in-residence featuring my trio with Dave Stryker and Kyle Koehler back to do the festival. I was given a Proclamation by the city, which was stunning to me. Then, John Scott opened his club and we started a great business partnership. We put on a very successful CD release event for the KC Generations Sextet “Acknowledgement” album and he gave me an open invite to come back and present my music. A lot of my relationships in Kansas City started to reignite. Including my relationship with Ahmad Alaadeen's wife Fanny. Through Fanny, I was a part of the Alaadeen Master/Apprentice Scholarship to have a young drummer study with me. I found a great young drummer in Patterson, New Jersey named Donovan Marshall. We started a relationship that was an incredible opportunity for both of us. He would go on to get accepted into Berkley and the New School. Last time I saw him he was playing a concert with Christian McBride, Shelia E and David Sanborn, so he’s keeping good company.

|

I also reconnected with Wes Faulconer, owner of Explorers Percussion and we’ve collaborated with the Canopus Drum Company on two clinics so far. He’s a great businessman and we talk for hours about music. His shop is incredible. We don't even have anything like that out here in New York. When I lived in Kansas City, Wes brought in people like Tony Williams, Dennis Chambers, Simon Philips. Man, that was like a dream come true to see Tony Williams play. KC is fortunate to have a world class drum shop like Explorers. Then I started doing clinics for Lee's Summit High School with their Band Director Scott Kuhlman. So, I got involved with the education aspect with Fanny, Wes and Scott. It's a part of the "Each One, Teach One" philosophy that I learned from Carvin. There was a whole other lifetime of people I connected with in KC, a lot of friends and family. Another one was Chuck Haddix. He's like a cool uncle to me. I worked at the Marr Archives for three years when I was in college. What he has done with those archives is unbelievable and his “Fish Fry” radio program is absolutely peerless, he’s in a class all his own. It just feels really good to reconnect with all of these people that feel like family. When I go back and see them all, it's healing. The thing about Kansas City is that they take care of their own, they support. I want to keep these relationships going. After traveling around and seeing other scenes, there is something special about the Kansas City scene. The listeners and the musicians take care of their own.

|

Let's talk about your latest CD - The Other Side of the Story - released last year. It's charting well and you teamed up with Carvin on this release. Talk to me about this album.

This album is the other side of my story as a composer and bandleader. I wanted to do an album of all original material and had a lot of songs, some of them finished and others not. I studied piano quite diligently for two years to gain the harmonic knowledge to expand on these tunes and finish them. This album is meaningful to me for that. I wanted to really present my musical vision as an artist. I can’t do that as fully as a sideman playing other people's music, but it definitely changes when it's your music. Some people can play other people's music and get to their art and be fulfilled, but for me to get my point across it had to be my music and my record.

So, Carvin came on board and once we booked the date, it was game on. I knew this was going to be on a high level. He's got a lot of experience making records. The way he guided us through the session as a producer, helped me see what a producer really is. Especially on “The Distance” Michael took us to the “other side” by helping us re-imagine our roles in the music, getting into a visualization. That’s producing, man. Carvin just had a great vibe in the studio going, we had a great time, listening to the sound.

This album is the other side of my story as a composer and bandleader. I wanted to do an album of all original material and had a lot of songs, some of them finished and others not. I studied piano quite diligently for two years to gain the harmonic knowledge to expand on these tunes and finish them. This album is meaningful to me for that. I wanted to really present my musical vision as an artist. I can’t do that as fully as a sideman playing other people's music, but it definitely changes when it's your music. Some people can play other people's music and get to their art and be fulfilled, but for me to get my point across it had to be my music and my record.

So, Carvin came on board and once we booked the date, it was game on. I knew this was going to be on a high level. He's got a lot of experience making records. The way he guided us through the session as a producer, helped me see what a producer really is. Especially on “The Distance” Michael took us to the “other side” by helping us re-imagine our roles in the music, getting into a visualization. That’s producing, man. Carvin just had a great vibe in the studio going, we had a great time, listening to the sound.

I brought in a dream band of musicians I have history with: Mark Peterson, a great bassist from St. Louis who has worked with Ornette Coleman and Stevie Wonder. The legendary Vic Juris who is a true individual artist of the music. And then there’s Klaus “in the house” Muller who is my buddy from the New School days and is an unreal pianist. We brought in Peter Schlamb from Kansas City on vibes who’s a true champion of the music, he brings it 100% all the time.

What I learned is that you’ve got to have a team. A bandleader is the ultimate team player. Especially a drummer. It’s about elevating the group. that’s what drummers do. You got to have a team and you’ve got to lead them, trust them, take charge and lay this music out and make it as easy as possible for them to come right on in and bring their artistry to the music. Ultimately it’s about elevating the group.

The other part of our team was a phenomenal mixing and mastering engineer named Dave Darlington. He's on 26th Street in the city and works with people like Wayne and Herbie and Sting, and Dave’s an artist of sound. We’ve done several projects together over the past 15 years. He and Carvin work really well together and we had a ball putting this record together. The way an album sounds is extremely important. Let’s accentuate the sounds, especially the drums! Not meaning volume, but richness of the tone. Drums are an instrument of indefinite pitch… that means it’s infinite what they can sound like. The drums sell the song, the drums are the thrust. I ain’t saying that because I’m a drummer, it’s just true.

Another very important part of the team is a brilliant artist named Debra Smith. She lives in Kansas City. We went to high school together in Hannibal and we both moved to New York in 1997. We both crossed paths once in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. She paid dues in NYC and then moved back to Kansas City and she's major talent in the art world. Her work is on the album cover. If you are going to be an artist, the whole project has to reflect that. In the design and everything. We also worked with a wonderful designer, Chris Drukker, for photography and design. He’s a deep cat who’s knows a lot about this music. That insight matters. You got to have an artist of sound to mix it, an artist of design to arrange the layout, etc.. If you are creating art, it has to be that from the ground up. We achieved that with The Other Side of the Story. It’s a team sport.

The album means a lot to me. We did well with it. WBGO picked it up in New York and put us on a program called The Radar and played it every other hour. Rhonda Hamilton did a beautiful write-up on the WBGO website and that meant a lot to me to be edified like that. Listeners were calling the station asking about “Hannibalian” which was the fan favorite song on the record. To hear my own compositions over New York City Radio was gratifying. Us drummers get stuck with these stigmas of not being real musicians. What some don’t understand is that the drummer is the key.

During the session sometimes session would bog down a little and Carvin would say “Next tune please.." He produced, he kept it fresh and moving forward. The further away from the spirit you get, the more it's going to sound contrived. People don't respond to diminished scale over whatever chord. The ultimate point is the feeling and the sound. Drummers got the feeling. When we did that record, that was the ultimate culmination of my life thus far. Everything clicked into place on that record. The magic that happens when you write a tune and bring it to cats and they bring it and they bring their take on it and it becomes larger than just you. Then when you get a team, focus them and it becomes bigger than the whole lot of us together. It transcends. Man, that’s what I love about music, it goes back to first hearing music from a vinyl disc, it’s that alternate universe, that dimension that transcends.

During the session sometimes session would bog down a little and Carvin would say “Next tune please.." He produced, he kept it fresh and moving forward. The further away from the spirit you get, the more it's going to sound contrived. People don't respond to diminished scale over whatever chord. The ultimate point is the feeling and the sound. Drummers got the feeling. When we did that record, that was the ultimate culmination of my life thus far. Everything clicked into place on that record. The magic that happens when you write a tune and bring it to cats and they bring it and they bring their take on it and it becomes larger than just you. Then when you get a team, focus them and it becomes bigger than the whole lot of us together. It transcends. Man, that’s what I love about music, it goes back to first hearing music from a vinyl disc, it’s that alternate universe, that dimension that transcends.

The world became much brighter after I got away from alcohol and began jumping rope. With, Klaus Mueller, Steve LaSpina and Vic Juris for SteepleChase Records date "Destiny"

The world became much brighter after I got away from alcohol and began jumping rope. With, Klaus Mueller, Steve LaSpina and Vic Juris for SteepleChase Records date "Destiny"

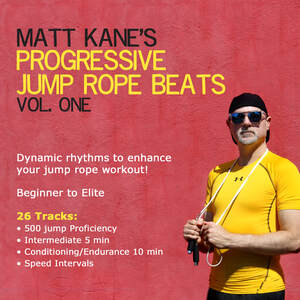

Talk about the rhythm of the jump rope and your cycling. How do all of those factors in to how you create?

The jump rope is a part of who I am. I learned to jump rope when I was boxing at a young age. I did not become a boxer, but kept doing the jump rope off and on thru life because it felt good. When I finished my days of drinking alcohol and put that in the rear view, I said “OK, we are done and we did that. Time to start living.” There was a lot of healing to be done. I dug myself a big hole, it wasn’t pretty. I dusted off my trusty friend the jump rope and said let me see if I can still do this. I started jumping and I got a smile on my face and I feel good and weight starts coming off. Folks are saying I look good. I'm sober and I'm moving in a positive direction. I meet Carvin and start playing with cats like Vic Juris and Steve LeSpina. It sounds dramatic but the jump rope helped me save my life. It’s true. See, jumping is a positive action. People “jump for joy”, right? It has a very positive effect on your brain, immediately. So, I took a rhythm that I heard while I was jumping rope and wrote a bass line, melody and groove to it. It sounded cool and inspired me to workout. Then, I put out an album called Progressive Jump Rope Beats Volume 1. It's got very slow tempos for people to start jumping to and then the tempos get progressively quicker. I released it in 2017 and I started getting emails from people in Australia, Japan, India and America and they were going wild over it. Then I got a visit from some folks who live in Mississippi that have a jump rope class at a YMCA down there. They had been using my album to teach the class. They said that it changed their lives. It was one of the more moving experiences of my life to meet a total stranger who used the jump rope album to not only help themselves, but to help their class. And cycling is another thing that I’ve returned to, I used to race BMX bikes when I was a kid and recently started road cycling. I just completed my first “Century” which is a 100 mile ride. The feeling of accomplishment from that is indescribable. Frankly, when you aren’t burdened with a bad habit, now there’s an open space for something good, human beings are creatures of habit, and I love jump rope and cycling and swimming because those speak to my personality. They’re groove exercises and life is a groove. It’s who I am.

The jump rope is a part of who I am. I learned to jump rope when I was boxing at a young age. I did not become a boxer, but kept doing the jump rope off and on thru life because it felt good. When I finished my days of drinking alcohol and put that in the rear view, I said “OK, we are done and we did that. Time to start living.” There was a lot of healing to be done. I dug myself a big hole, it wasn’t pretty. I dusted off my trusty friend the jump rope and said let me see if I can still do this. I started jumping and I got a smile on my face and I feel good and weight starts coming off. Folks are saying I look good. I'm sober and I'm moving in a positive direction. I meet Carvin and start playing with cats like Vic Juris and Steve LeSpina. It sounds dramatic but the jump rope helped me save my life. It’s true. See, jumping is a positive action. People “jump for joy”, right? It has a very positive effect on your brain, immediately. So, I took a rhythm that I heard while I was jumping rope and wrote a bass line, melody and groove to it. It sounded cool and inspired me to workout. Then, I put out an album called Progressive Jump Rope Beats Volume 1. It's got very slow tempos for people to start jumping to and then the tempos get progressively quicker. I released it in 2017 and I started getting emails from people in Australia, Japan, India and America and they were going wild over it. Then I got a visit from some folks who live in Mississippi that have a jump rope class at a YMCA down there. They had been using my album to teach the class. They said that it changed their lives. It was one of the more moving experiences of my life to meet a total stranger who used the jump rope album to not only help themselves, but to help their class. And cycling is another thing that I’ve returned to, I used to race BMX bikes when I was a kid and recently started road cycling. I just completed my first “Century” which is a 100 mile ride. The feeling of accomplishment from that is indescribable. Frankly, when you aren’t burdened with a bad habit, now there’s an open space for something good, human beings are creatures of habit, and I love jump rope and cycling and swimming because those speak to my personality. They’re groove exercises and life is a groove. It’s who I am.

This next question is a future one. You have an album slated for 2020. So, give me a look into this new project and what the future holds for Matt Kane.

On the next album, I want to work with vocalists. I don't know if I'll write as much for this one, but I'd like to visit songs that made me want to play music. I have some songs in mind. The reason I want vocalists on this because I want to connect with people through the voice. Not in a commercial sense to sell more CDs, but I want a more personal connection with this and not as much soloing. I want to emphasize the song more. Carvin will be producing again, too. That's coming up. The other thing is the Matt Kane School of Drumming. We are getting ready to do our 9th Annual Day for Drummers Recital. I'm going to continue to work with all of my great young drummers. They are a healing force in my life. We will be coming up on 10 years next year. Teaching is very important to me, I’m deeply dedicated to these kids and their success. A win for them is a win for me and a win for the music. I will put out another jump rope album in 2020. I have had a lot of requests for that and I have fresh ideas for it. I will probably be doing a lot more piano study and writing. In 2020 I will be performing a lot more with my group, too. I do play out with the group now, but I will be stepping that up in 2020. I’ll be in KC to do a collaborative show with Debra Smith on Sunday, November 17th at Studios Inc. That’s gonna be a special show so keep an eye out. Kansas City will always be special to me, the place, the people and the music.

On the next album, I want to work with vocalists. I don't know if I'll write as much for this one, but I'd like to visit songs that made me want to play music. I have some songs in mind. The reason I want vocalists on this because I want to connect with people through the voice. Not in a commercial sense to sell more CDs, but I want a more personal connection with this and not as much soloing. I want to emphasize the song more. Carvin will be producing again, too. That's coming up. The other thing is the Matt Kane School of Drumming. We are getting ready to do our 9th Annual Day for Drummers Recital. I'm going to continue to work with all of my great young drummers. They are a healing force in my life. We will be coming up on 10 years next year. Teaching is very important to me, I’m deeply dedicated to these kids and their success. A win for them is a win for me and a win for the music. I will put out another jump rope album in 2020. I have had a lot of requests for that and I have fresh ideas for it. I will probably be doing a lot more piano study and writing. In 2020 I will be performing a lot more with my group, too. I do play out with the group now, but I will be stepping that up in 2020. I’ll be in KC to do a collaborative show with Debra Smith on Sunday, November 17th at Studios Inc. That’s gonna be a special show so keep an eye out. Kansas City will always be special to me, the place, the people and the music.

Services |